MILLIE’S MYSTERIOUS LETTER

- David Farah

- Oct 11, 2023

- 5 min read

Updated: Oct 12, 2023

The common usage of ‘hack’ today refers to getting unauthorized access to someone’s computer, or a time or labor saving shortcut. When I was young, the term had a different connotation, that of a pejorative for a writer of little skill producing uninspired prose for an uneducated audience. Often, ‘hack’ was used to mean a ghost writer fleshing out a story for someone more notable who got the credit and most of the remuneration, someone little better than a glorified editor. If you moved up the social scale, you got to be ‘a writer’ and then ‘an author.’

My files contain the only complete set of the private papers of Mildred Lillian Augustine Wirt Benson. The majority of the Benson papers are accounting documents Millie kept for tax records, or were outlines or research material for stories both published and unpublished. More interesting were private letters, giving an insight to both personal and business affairs. One such document is reprinted here, a single sheet, the first page of a letter composed by an unnamed correspondent. The identity, however, is clearly the author Roy Judson Snell based on the content of the letter. Based on the internal clues, I believe that the letter from Snell was composed in the fall of 1944 replying to a letter probably composed weeks earlier.

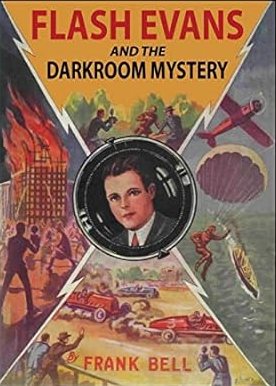

Roy Judson Snell (born in Laddonia, Missouri on November 12, 1878 and died September 21, 1959) had his first book Little White Fox and His Arctic Friends published in 1916 (based on his experiences as a missionary in Alaska). Between 1916 and 1944, he is credited with over 80 volumes of children’s books. Published under his own name and a few pseudonyms, most of Snell’s works were stand-alone adventure or mystery books, but he also wrote the eight volume Radio-Phone Boys series (1922-1928), the three Fighters For Freedom Series published in 1943 and, more likely recognized by this readership, the four A Jimmy Drury (Story/Mystery) 1936-1941 under the pseudonym David O’Hara. During my early years of collecting, his books were widely available in used bookstores evidencing their original popularity.

The letter in question begins “Dear Mrs. Wirt” which tells me that Millie and Roy were not well acquainted. Millie hated being called “Mrs.” anything and would tell you so. Millie explicitly requested to be called “Millie” or “Mil.” I chose “Millie.” In personal correspondence to friends, Millie generally signed the correspondence “Mil” or “MB.”

I’m going to skip the first paragraph of the letter to go directly to the brief two sentence second paragraph:

No more radio contracts, don’t seem to come my way. Jack Armstrong changed writers but a Boy’s Life editor got the job.

The character Jack Armstrong originated as a marketing tool for General Mills’ breakfast food Wheaties in 1926. The character was featured in a two volume book series released by Cupples & Leon in 1936 (Jack Armstrong's Mystery Eye and Jack Armstrong's Mystery Crystal), two Big Little Books (Jack Armstrong and the Ivory Treasure, 1937; Jack Armstrong and the Mystery of the Iron Key, 1939), a 1947 Columbia film serial Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy, and a thirteen issue comic book series (Parents Institute publisher, November 1947-September 1949). Most prominently, however was the Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy radio adventure series running from 1933 to 1951 syndicated on CBS, NBC, Mutual, Blue Network and finally ABC.

Radio was the streaming service of its day employing tens of thousands of workers nationwide and requiring a seemingly endless need for externally provided content–in this case, scripts to be performed on the air. Snell contributed scripts to the radio show in 1941.

Now the events leading up to the letter and the second paragraph. Millie married Asa Wirt in 1928 in lieu of returning home from college to live in Ladora Iowa without a secure income. After years of work writing short stories and then children’s books, Millie finally made enough in royalties and selling completed manuscripts to be self-supporting by the late 1930s. Millie gave birth on November 6, 1936 to Margaret (Peggy) Wirt. Never intending to have a child and wanting nothing to do with motherhood, Millie turned over the duties of raising Peggy to Peggy’s grandmother Lillian, who came to live with Millie and Asa.

Then the children’s book market changed. Comic books took off in 1939 and 1940 cutting deeply into the profitability of children’s books. World War II regulations in 1942 decreased the paper supplies available. In the space of a few years, Millie’s main publishers Cupples and Leon and Goldsmith stopped publishing Millie’s books.

If that wasn’t enough, Asa, twenty years Millie’s senior, had a stroke and became an invalid not contributing to the family income. By the summer of 1944, Millie had no choice but to “officially” cease trying to make a living as an independent writer and to take a job with the local Toledo paper, the Toledo Blade and Times, as a reporter and editor covering the local political news. Millie was told that the job would only last until the soldiers returned from fighting, that is ‘war work.’

Now, back to Jack Armstrong. Millie knew that the market for children’s books would not provide enough support and attempted to break into the more lucrative radio script market creating a complete manuscript for Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy. The manuscript was eventually rejected, but Millie had sent the manuscript to a rather famous author for review and advice (another story) and, I think, also contacted Roy Snell as a contributor to the program seeking advice. Hence, in the second paragraph of the letter Snell simply informed Millie that Snell had no influence with the powers that be on the Jack Armstrong radio show; and that Snell, himself, was in fact effectively fired as a script writer.

Now we come to the first paragraph:

I don’t like your attitude toward your writing and mine. We are not hacks! Anyway there are ten thousand writers who would be glad to strut the books we have written. So what! In my time I’ve written for all the best juvenile magazines and had Chas. Livingston Bull illustrate a whole series of my stories. I’ve done five books for Little Brown, than which there are none more highbrowish. I’ve made the Amer. Library assn. three or four times and had a million and a half books sold. Good God! What must one do to get out of the HACK class! Well, that’s that.

I believe that Millie had informed Snell of the loss of income and being unable to obtain sufficient commissions, and had used the word ‘hack’ to describe both of their products because of the little value their prior successes meant at the present time. Snell took unintended offense. Obviously, this was not the first time Snell had been denigrated as a ‘hack.’ (It wasn’t Millie’s either.) Snell laid out his case for being not only successful but not ‘hackish.’

Then, the third paragraph, which begins: “So you got a job? I could do defense work and make a lot of dough, . . .” This implies that Millie had related the supposed temporary nature of the Toledo Blade and Times reporter job. Snell goes on to relate his financial situation, including that his work on the Jack Armstrong radio program was salaried, not free-lance. The remainder of the extant letter is, well, puffery, as if he needed to compete with Millie’s successes. (Let’s face it, no work of Snell ever received the notoriety of Nancy the Drew series and they both knew it.)

One thing I heard from authors and artists alike is that producing creative content for a living is not glamorous but hard work, and underappreciated by consumers. This letter gives us consumers an insight to the struggles of those authors . . . hackish or highbrowish.

Comments